By Sonny Onyegbula

Human rights enforcement in Nigeria inhabits many complexities such as the enforcement mechanisms for court judgements, which tend to hinder progress. Other issues relate to prolonged cases, judicial timidity, and interference from the executive and politically exposed individuals.

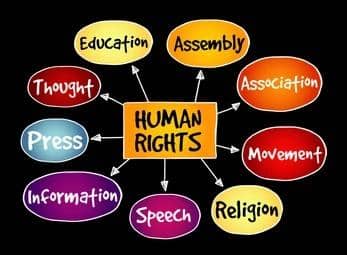

Nigeria’s 1999 Constitution (as amended) has provisions for a set of fundamental human rights, indicating the country’s commitment to the principles of justice and equality, with nuanced understanding of the interplay between individual rights and state obligations.

Human rights protected by the Nigerian Constitution include the right to Life (Section 33), right to Dignity (Section 34), right to Freedom of Expression (Section 39), right to Fair Trial (Section 36), Personal liberty (Section 35), Privacy (Section 37), Freedom of movement (Section 41), Freedom of association (Section 40), rights of persons with disabilities (Section 42), and right to Education (Section 18).

However, the rights to economic benefits, education and healthcare are non-justiciable, underpinned by inadequate resources and the lack of political will for implementation, and this underscores the need for more aggressive advocacy.

Also, despite the robust legal framework, the enforcement landscape reveals a disconnect between the normative instruments and the reality. Human rights violations, impunity, and institutional inertia underscore the need for a more effective accountability mechanism, judicial reform, and a cultural shift towards rights-based approach to governance.

Strengthening institutional capacity, ensuring judicial independence, and fostering a culture of transparency, accountability, and respect for human rights are essential to protect human rights in Nigeria. This requires a concerted effort by all stakeholders, including the government, civil society, and individuals, to ensure that the rights enshrined in the Constitution are enforced and protected.

The importance of enforcing court judgements to an effective justice system cannot be overstated. It is a fundamental aspect of the rule of law and a critical component of human rights protection. Legal scholars, human rights activists, and judges have consistently emphasized the crucial role of the judiciary in enforcing court judgements.

The consequences of non-enforcement of court judgements are many and far-reaching, including the erosion of trust in the judiciary and the rule of law. Persistent human rights violations and impunity can undermine the integrity of the legal system. In addition, the lack of enforcement of court judgements, entrenches human rights violations.

Additionally, the government and other stakeholders must work collectively to create the enabling environment for the enforcement of court judgements to promote human rights, accountability and the entrenchment of a justice system that meets international standards.

The approval or permission of the Attorney General of the Federation is required to enforce monetary judgements against state agencies, but executive interference and political pressure hinder the enforcement of court decisions.

South Africa has a track record of enforcing court decisions, particularly those related to human rights. Two notable cases demonstrate this commitment:

In Makwanyane v. South Africa (1995): The Constitutional Court abolished the death penalty, upholding the right to life, while in the Khosa v. South Africa (2004): The same Court ordered the government to provide housing, which comes under socio-economic rights.

Another judicial system that upholds the rights of individuals and ensures enforcement of court decisions to a very large extent is that of India.

In Maneka Gandhi v. India (1978): The Supreme Court established the right to life and liberty, including the right to a fair trial. Similarly, in Olga Tellis v. India (1985), the apex Court also ordered the government to provide housing, under the socio-economic rights.

The Indian Supreme Court is committed to prioritizing judicial independence, curbing executive interference and corruption, and ensuring effective enforcement mechanisms.

The U.S. Supreme Court has also demonstrated, through decided cases, a commitment to the protection of citizens’ right and promotion of social justice. For instance, in Marbury v. Madison (1803), the Supreme Court established a judicial review, a process where the apex court can review the constitutionality of laws or legal actions, to ensure the enforcement of constitutional rights.

In Brown v. Board of Education (1954), the same Court also ordered desegregation and enforced equal protection rights.

Britain is not left out as seen in Entick v. Carrington (1765), where the UK highest Court established the right to privacy and judicial review, setting a major precedent for protecting individual rights.

Also, in R v. Secretary of State for the Home Department (2013), the UK Supreme Court ordered the government to respect human rights in deportation cases, demonstrating the court’s commitment to upholding human rights and the rule of law.

To address bottlenecks on the enforcement of court decisions, Nigeria must prioritize judicial reforms, ensure independence of the judiciary, and deal with the systemic barriers that prevent marginalized groups from accessing justice. The legal profession must also uphold ethical standards and promote access to justice for all.

It is obvious that the U.S., UK, South Africa, and India have demonstrated different approaches to human rights enforcement, with unique strengths and weaknesses.

In the US, the Constitution and the Bill of Rights provide a robust framework, with the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) playing a crucial role in enforcement through litigation and advocacy. However, the system also faces some challenges such as the politicization and erosion of civil liberties.

In contrast, the UK’s Human Rights Act 1998 offers a more comprehensive approach, incorporating the European Convention on Human Rights and providing individuals with a clear avenue for redress. The UK Human Rights Council promotes and protects human rights, although the system now faces some challenges related to Brexit.

South Africa’s Constitution has progressive provisions on human rights and social justice, with the South African Human Rights Commission playing a vital role. However, poverty, inequality, and access to justice also hinder enforcement.

India’s Constitution enshrines fundamental rights such as the right to life, liberty, and equality. However, issues related to poverty, discrimination, and state repression remain a blight on the country’s human rights record. There are also issues related to corruption and inadequate access to justice.

No judicial system is perfect, but Nigeria can draw useful lessons from other countries’ experiences and insights for transformational changes in its system. This will make sure that adoption of a comprehensive approach to strengthen the independence and impartiality of the judiciary, are more transparent with merit-based appointments, and increased access to justice and legal representation for marginalized groups.

There is also the need for regular training for judges and other judicial officers, the police and security agencies, to equip all stakeholders with adequate knowledge on issues related to human rights and the rule of law.

The reform to Nigeria’s judicial system should also combat corruption and ensure accountability. It should involve relevant stakeholders for inclusiveness, to ensure buy-in and collective ownership.

Dr Sonny Onyegbula is a U.S.-based Legal Consultant

![]()

The learned author has not quoted a single case law out of the thousands of case law emanating from Nigeria upholding fundamental human rights pre 1999 during the military interregnum and post 1999 in the current democratic dispensation. It is very disappointing when so called learned scholars ignore the wealth of case law in Nigeria while purporting to do a comparative analysis of the human rights judgments which excludes the judgments from Nigerian courts.

Dear Madam, Thank you for sharing your thoughts. We take feedback very seriously, so we have forwarded yours to the author of the article.