By Chidi Anselm Odinkalu

Honourable Justice Emmanuel Obioma Ogwuegbu was part of a generation in which judging was a deservedly elevated calling. In return, society honoured people like him with the honorific “My Lord”, an acknowledgement that they were called to a job that is truly divine. Today, the senior-most lawyers publicly twerk to partisan orchestras conducted by people who were in professional diapers when they were already in the Inner Bar and judges are made to believe it is kosher to enjoy political joyrides and be serenaded with four-wheel bribes by politically exposed persons.

Phillip Adenekan Adekunle Ademola had everything it took to pursue an excellent judicial career at the highest level. He was the grandson of a king, the son of a Chief Justice and a prince in his own right. In another era, he could easily have become the first second-generation Chief Justice of Nigeria, CJN. It was his destiny to make neither and many still believe that he could have been the ablest Justice of the Supreme Court Nigeria never had.

Born on 27 July 1926, Adenekan Ademola completed his high school education at Kings College in Lagos in 1944 and attended Higher College, Yaba before proceeding to the University of London where he graduated with a law degree. When he qualified as a lawyer in 1951, his dad was already a judge, only the third Nigerian, to be so appointed. Adenekan Ademola practised law for the next 19 years and spent three working as Chairman of the Finance Committee of the Egba Divisional Council in present-day Ogun State.

When General Yakubu Gowon’s administration gazetted his appointment as a judge of the High Court of the Western State of Nigeria on 18 June 1970, Adenekan Ademola was just 45 years old. His dad, Sir Adetokunbo Ademola, an Egba blue blood, had been in office as the CJN for 12 years and two years before retiring as CJN.

In 1977, five years after he was appointed a judge, another soldier, Olusegun Obasanjo, elevated Adenekan Ademola into the pioneer cohort of justices of the Court.

A product of the mostly diffident judicial philosophy of the military era, he did not let the soldiers down. When some pesky Taiwanese litigants approached his bench in the Court of Appeal to hold the military to account for what looked like an evident violation of human rights, Adenekan Ademola elegantly counselled judges to “blow muted trumpets.” It was only a matter of time, many thought before his diligent service was requited by setting him on his way to follow in the footsteps of his celebrated father to the Supreme Court. Many made it there who had but a fraction of his ability and preparation.

On more than two occasions, Adenekan Ademola was actively considered for elevation to the Supreme Court. He had the intellect and pedigree for the role, and no one could accuse him of judicial Levitas. In the end, it was not to be. There was a persistent objection from another scion of an equally famous Egba dynasty who relentlessly levied serious complaints against Adenekan Ademola, which were never dispositively determined. But that was considered enough to ultimately park his judicial career in the cul-de-sac of the Court of Appeal. In 1991, Adenekan Ademola retired from the Court of Appeal. Reflecting his cultured intellectual outlook, he was later appointed the inaugural Director of Studies of the National Judicial Institute.

In those days, judicial integrity was taken seriously and even the slightest whiff of integrity deficit or exposure attracted career consequences. Sir Olumuyiwa Jibowu was the first Nigerian Justice of the Supreme Court. His reputation as a judge appeared impeccable. In 1957, it emerged that Sir Olumuyiwa had written a letter to an old friend, one Mr Savage, which was said to have content that made references considered to be insalubrious about the leader of the National Council of Nigeria and Cameroons (NCNC), Dr Nnamdi Azikiwe. One year later, when his name came up for consideration to become the first indigenous CJN, the content of the letter was enough to force Sir Olumuyiwa’s withdrawal from contention. The beneficiary was Adenekan Ademola’s dad.

Today in Nigeria, closeness to politicians is widely perceived to be a boost to judicial ambitions, not a constraint. A Federal High Court judge has recently gone on record to say that to be appointed a federal judge today in Nigeria, “one must either have the backing of the presidency or a political party.”

A widely respected continental medium recently reported under the caption “Why Nigerian judges love Nyesom Wike”, that the Minister of the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) is “lauded like a rock star in judicial circles.” Part of the reason for the judicial superstardom of the FCT Minister is his material “generosity” towards judges.

This was not always the standard judicial fare.

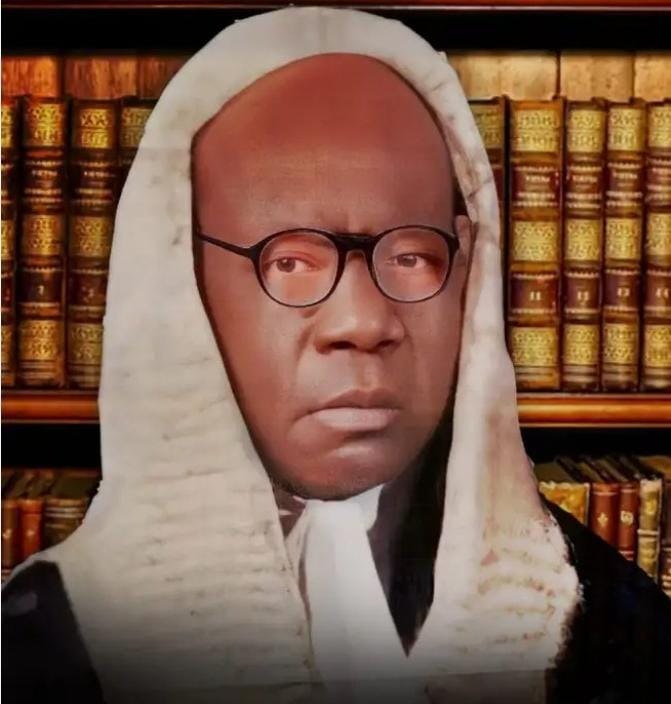

The 1983 elections in Nigeria were quite contentious. Those were the first to be supervised by civilians under the presidential system. Many of the disputes over election outcomes ended up in court. Emmanuel Obioma Ogwuegbu, whose death at 91 recently became public, was then a judge of the High Court of Imo State. He later joined Adenekan Ademola in the Court of Appeal. The year after Adenekan Ademola’s retirement, Ogwuegbu proceeded to the Supreme Court, where he served for 11 years before retiring in 2003.

One night shortly after the 1983 elections, Obioma Ogwuegbu received an unusual night-time visitor at his official residence in Aba. Onyeso Nwachukwu who died in 2022 was a pious man, an Elder in the church, and the state chairman of the ruling National Party of Nigeria (NPN). On this night, the party chairman arrived with his wife, who blagged her way into the house by dropping the fact that she was a high school contemporary of the judge’s wife at the Community Girls Secondary School, Elelenwo, Rivers State.

Under the guise of a social visit, the party chairman visited to plead the cause of the beaten NPN governorship candidate, Collins Obi. The election petition was yet to be heard and the panel to hear it was not even announced. But the party wanted to advance the judge onto the panel as its “person.”

Obioma Ogwuegbu firmly reprimanded him before ushering him out of the house.

On the grounds of the compound but unknown to the judge, the party chairman had parked a brand-new Range Rover car complete with cellophane frills. As Justice Ogwuegbu ushered him out of the house, he noticed the party chairman walking to slide into another well-appointed sedan. So, he asked who the owner of the new Range Rover was. In response, the party chairman sidled up to the judge to inform him that he was the proud recipient of the four-wheel gift for his end of year.

Obioma Ogwuegbu smiled and pleaded with the party chairman to spare him further hardship. He explained that he had enough problems maintaining his Mercedes Benz car on his judicial salary and could not afford the financial exposure of trying to maintain an exponentially more expensive car. He insisted that the party chairman had to go with the car in the same manner that he brought it onto his compound. Obioma Ogwuegbu later begged off election tribunal duty because of this.

With reluctance, Elder Onyeso Nwachukwu drove out in the Range Rover which was manifestly meant to bribe an honest judge. For the remainder of his life, however, he lived in awe of Obioma Ogwuegbu because, he said, the judge belonged to that rare breed who could not be bought.

Honourable Justice Emmanuel Obioma Ogwuegbu was part of a generation in which judging was a deservedly elevated calling. In return, society honoured people like him with the honorific “My Lord”, an acknowledgement that they were called to a job that is truly divine. Today, the senior-most lawyers publicly twerk to partisan orchestras conducted by people who were in professional diapers when they were already in the Inner Bar and judges are made to believe it is kosher to enjoy political joyrides and be serenaded with four-wheel bribes by politically exposed persons.

There will be time to return to the matter of how judicial integrity descended into their current morass and to address what can be done about that. For the moment, it is time to honour the memories of a generation of men and women, epitomised by Emmanuel Obioma Ogwuegbu, who put the “honourable” into the appellation, “Honourable Justice.”

A lawyer and a teacher, Odinkalu can be reached at chidi.odinkalu@tufts.edu

![]()