Lately, Abuja has embarked on signing or deepening defence partnerships with the United States, China, the United Kingdom, Russia, France, India, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan and now, Türkiye, often within overlapping time frames and against a backdrop of unrelenting insecurity. On paper, this looks like strategic diversification. But given Nigeria’s weak institutions and fragmented loyalties, these multi-power deals risk multiplying internal vulnerabilities rather than delivering autonomy.

In international relations, hedging is meant to be a sophisticated strategy. Middle powers cultivate ties with rival blocs at the same time; securing trade, weapons, intelligence and diplomatic cover from each without fully joining any camp. Done well, hedging buys room to manoeuvre in a fluid world.

However, successful hedging demands a coherent centre. It assumes the state has a clear hierarchy of national interests, reasonably disciplined security institutions, and a political class that can resist turning every external relationship into a patronage asset. Nigeria does not enjoy those conditions. The federation remains riven by sharp regional, ethnic and religious cleavages. Security agencies are still deeply exposed to politicisation, often shaped by “loyalty clubs” and patron-client networks rather than by doctrine.

When you pile complex, overlapping military partnerships on top of a jaundiced domestic terrain, what you get is a crowded and inflamed marketplace in which foreign and domestic actors bargain over influence with contaminated information.

The recent pattern is revealing. With Washington, Nigeria has moved into a new phase of security cooperation: advanced air platforms, intelligence-surveillance-reconnaissance support, kinetic assistance against extremist camps, and a growing noncombat troop presence focused on training, coordination and operational support.

London has formalised a Security and Defence Partnership with Abuja on doctrine, special operations, maritime awareness and joint planning. Paris, too, is embedding itself through operational training and intelligence cooperation in the Sahel and Lake Chad basins.

At the same time, China has stepped in as a defence-industrial partner, promising technology transfer and local production of ammunition and advanced equipment. Moscow maintains a framework for training and equipment supply, while Riyadh has concluded a renewable defence memorandum covering training, logistics, counter-terrorism and intelligence.

New Delhi and Islamabad both court Abuja with staff talks, courses and high-level visits. For its part, Türkiye has upgraded its role from arms supplier to full-spectrum partner with Nigeria, combining drones, helicopters and naval platforms with special forces training and real-time intelligence.

Add ECOWAS, the African Union, the UN and smaller bilateral channels, and Nigeria’s security ecosystem is now densely populated with external actors, many of whom are rivals among themselves and carry their own regional agendas.

From Abuja’s official podium, this is sold as diversification and a strengthening of “defence architecture”. However, from the vantage point of a fragile bureaucracy, it looks more like a multi-layered web, too complex for the state to see, let alone control.

In its current fragile state, Abuja risks overestimating its capacity to juggle many rival interests at once. Great powers can absorb shocks and play multi-board games; a state with weak institutions and contested loyalties cannot.

When external hedging meets internal fragmentation, rival domestic factions increasingly hitch their loyalties to different external partners. One elite unit becomes the Americans’ partner of choice; another cluster is drawn to Russian or Chinese; religious and cultural affinities pull others toward Saudi Arabia, Pakistan or Türkiye; while historic and educational ties still make British links the default home for another group.

Over time, these alignments risk consolidating Nigeria into a patchwork of “mini-Nigerias”, divided along old ethno-regional and religious fault lines. But the greatest risk would appear in information and intelligence sharing.

What was designed to widen access to intelligence, military equipment and expertise risks degenerating into counter-hedging platforms. Trust dies in the hands of competing layers of interests, and doubts about Nigeria’s ability to prevent leaks of valuable information multiply. Gradually, the partners stop treating Nigeria as a trusted ally and instead see her as a contested space to be monitored and managed.

The Horn of Africa offers a cautionary story. Over the past decade, states around the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden have welcomed bases, training missions and facilities from almost every major military actor: the US, China, European navies, Gulf states, Türkiye and others.

It is instructive that external militarisation has not stabilised the region. Parts of Somalia, for example, saw courting foreign interest as a route to de facto independence and recognition. Neighbouring nations and distant powers alike treated ports, coastal enclaves and airfields as instruments in larger rivalries.

Although Nigeria is vastly different from the Horn of Africa, the logic is uncomfortably familiar. When many external actors plug into a fragile political-security ecosystem, they amplify fractures and turn domestic disputes into wildfires.

Certainly, Nigeria should have partners. Isolation is neither realistic nor desirable. Strong, coherent middle-power states can hedge because they possess the institutional spine to decide who does what, where, and on whose terms. Weak, divided states hedge at their peril. For Nigeria today, multiplying security deals without first consolidating doctrine, professionalising institutions and building a minimal national consensus risks crossing that line.

Nigeria’s leadership like to speak of strategic autonomy, but sovereignty is not the ability to sign more MoUs than your neighbours. It is the ability to say “yes” and “no” from a position of internal strength. Abuja must now invest seriously in developing its own strength, its multi-power security systems. Diplomacy will remain a dangerous overexposure when we invite the world into our house, when our foundations are still visibly cracked.

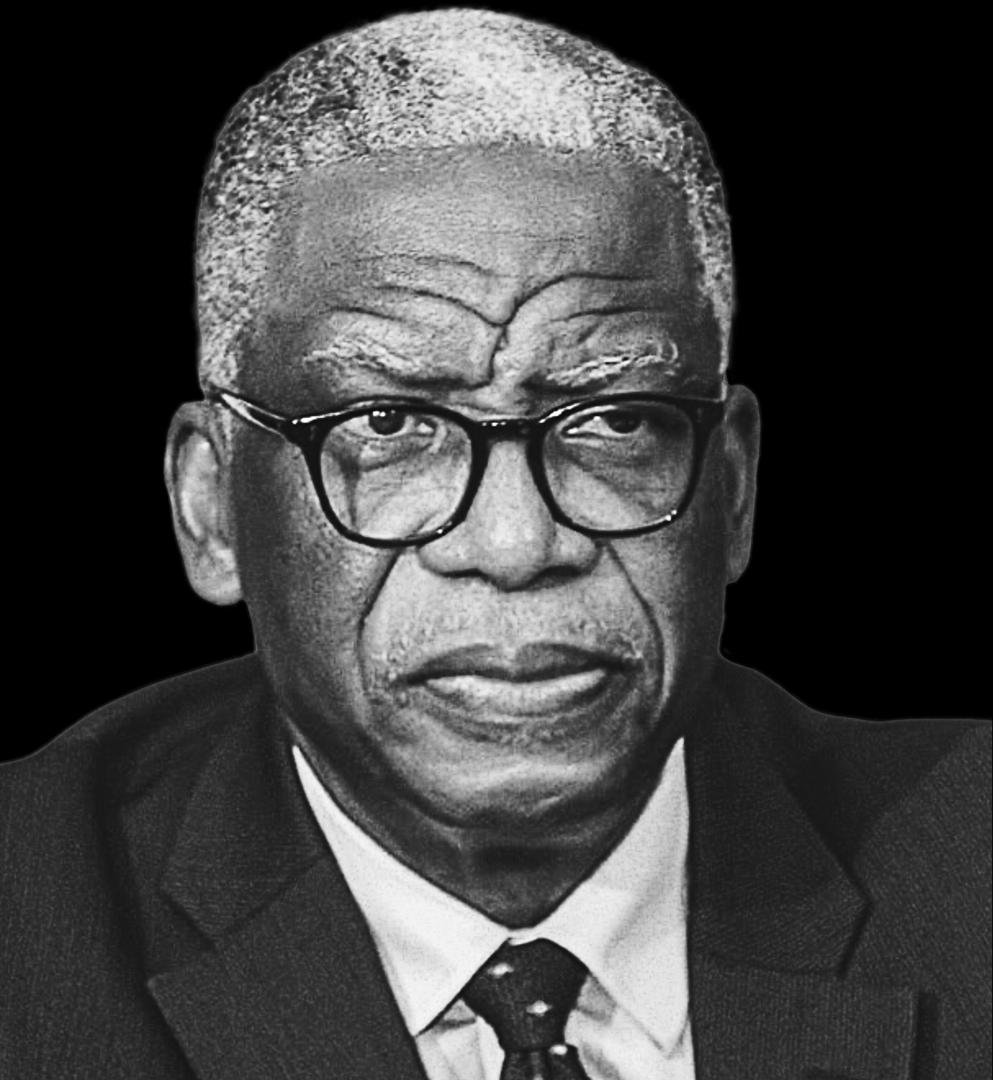

Dr Richard Ikiebe is a Media and Management Consultant, Teacher and Chairman, Board of Businessday Newspaper

![]()