It takes enormous courage, strong will and conviction to share the inner secrets of a personal life, with all the misfortunes, the bad and the ugly, including childhood abuse, a turbulent marriage, cultural taboos, and racial discrimination at work, even when all ends in exceptional successes.

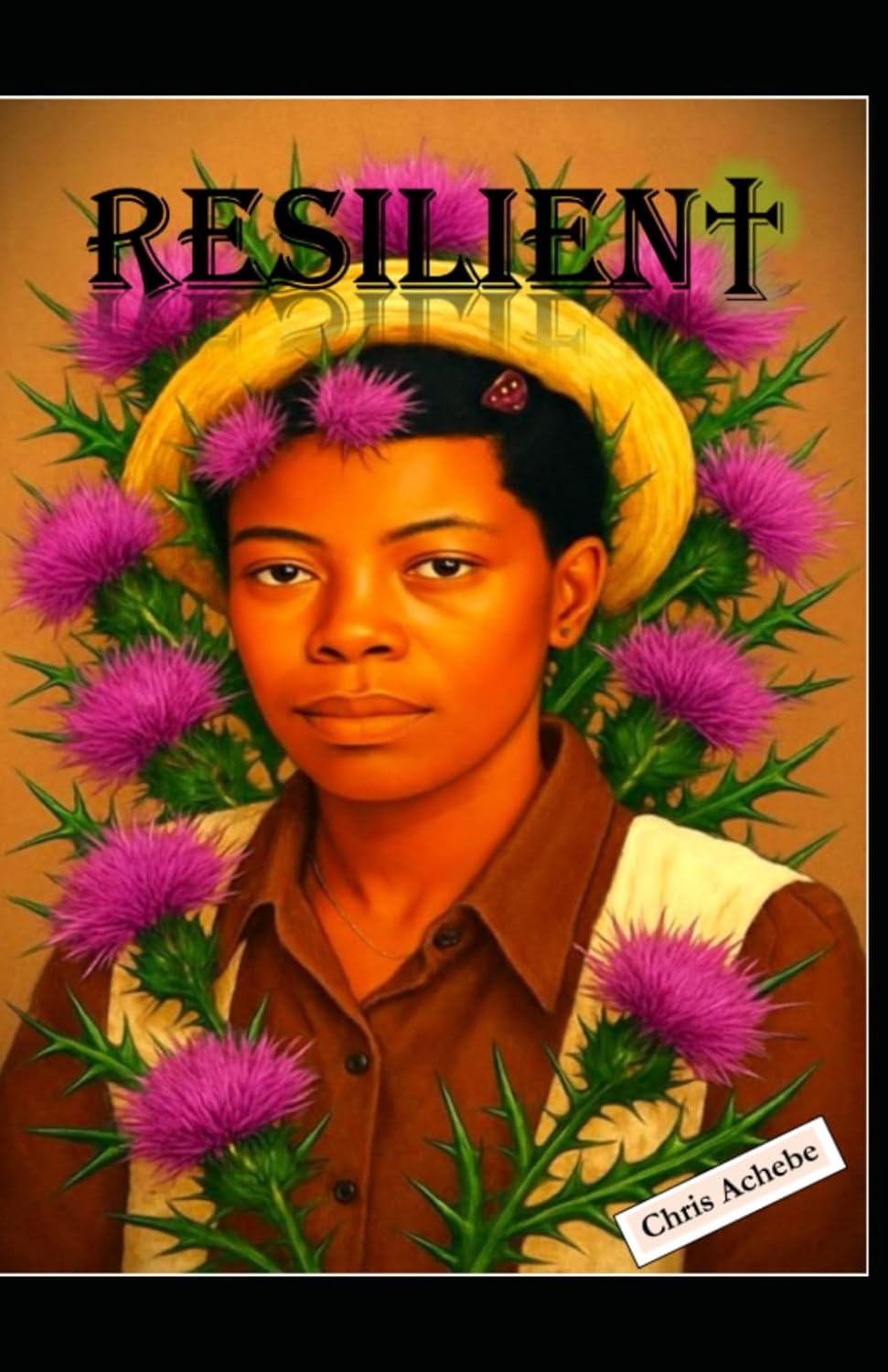

That is exactly what Resilient is about. A 425-page memoir of Christina Kanayo Achebe-Mordi, a Registered Nurse (RN), Legal Nurse Consultant (LNC) with a Doctorate in Professional Studies (DPS), focusing on Bioethics and almost three decades’ professional experience in the US.

Christina took the ‘Ada’ moniker in the memoir, a child from a poor background in a community with cultural, religious and traditional practices among the Igbo of Eastern Nigeria and many other African societies.

Rising from the scars and traumas of child abuse, challenged adulthood, an abusive marriage, involving intermittent separations/estrangement, and being forced to perform traditional rites of reconciliation after the husband absconded, Ada endured a painful motherhood and widowhood. Still, she transformed herself into an advocate and champion of voiceless children and women victims of what she went through.

Resilient is a collection from Ada’s diligently kept diary, partly written in Pittman’s shorthand, translated into four engaging chapters of captivating stories. It sheds light on some undiluted truths rarely spoken aloud, such as incest and other atrocities that linger in the shadows of Igbo/Africa cultures as secrets but shameful realities of many families.

Chapter one begins with the story of Ada’s mother, Mma’s unplanned pregnancy, and how Umeadi, her secret lover responsible for the pregnancy, and who later became her husband and Ada’s father, deserted Mma in Abba village in the present-day Anambra State, South-Eastern Nigeria.

Mma herself, the first daughter among five siblings (three girls and two boys), had experienced hard labour in her village. It was while running errands that she met Umeadi, who escaped to Lagos due to the pregnancy.

Even after giving birth to a baby boy, Uche, Mma still endured the wrath of the powerful Umuada, the women’s group of the community, who must administer the mandatory rites of punishment to any woman who had a child outside wedlock.

“What were you thinking? That nobody will catch you when you are frolicking in sin? Whoever did this (pregnancy) to you? Well, it is not his fault because you… did not close your legs,” the women leader chastised. Absorbing the ridicule in silence, Mma’s tears flowed and dropped on her innocent baby.

The memoir uses Mma’s case to illustrate the plight of millions of Nigerian/African girls saddled with unplanned pregnancies, many resulting in deaths and high maternal mortality rates.

After many months, Umeadi’s kinsmen sent emissaries to him in Lagos about Mma’s status and counselled marriage between them. Umeadi owned up to being the father of Mma’s pregnancy but was unprepared for child’s care. It took about five years after Ada’s elder brother was born before Umeadi’s family elders went to Lagos to force him home and marry Mma.

When Mma eventually joined Umeadi in Lagos, he had a live-in lover. All the same, he and Mma had a white wedding at St. Dominic’s Catholic Church, Yaba, Lagos, in 1961. Even so, the arrival of Ada (the first female child in Igbo), and the second child in Umeadi’s family was not what Mma expected. In Igbo land and many African cultures, a woman’s life revolved around the patriarchal man’s world. Umeadi had wanted another male child and openly told Mma: “She (Ada) is a girl and, therefore, another man’s property… of no significance in my home.”

At his dilapidated ghetto home in Abule Ijesha, Lagos, Umeadi thrived as a squatter landlord. He also became notorious for disappearing from home to escape his parental responsibilities.

Chapters two and three capture Mma’s pains, humiliation and difficulties in raising her children in the slum without emotional or financial support from Umeadi. To console herself, she usually sang native songs and told her children teachable life stories, which resonated with little Ada, who enjoyed her mother’s songs more than her lengthy prayers.

In an era of ground latrines and open defecation, Ada fell ill frequently and had ugly encounters with the hooded night-soil men, the “agbepos” in her community that lacked water-system toilets, and where shack dwellers tapped electrical energy to light up their homes and petty business centres.

Ada remembers her father’s gambling, drunkenness and her being rescued from drowning in the shanty flood, an incident that earned her the wrath of her mother, but ignited her Christian faith and closeness to God, through constant prayers.

Umeadi and Mma were blessed with four children: Uche, Ada, Echi, and Friday (three sons and a girl) before the Nigerian Civil War of 1967-70 broke out, when the Igbo of southeastern Nigeria unsuccessfully attempted to secede as independent Republic of Biafra. Umeadi was drafted into the civil war, while Mma took their four children to Abba village, in eastern Nigeria, like most Igbo people did then. Umeadi had no home in the village, so Mma was given a space in her in-laws’ home with strict instructions to fend for her children.

In the village, Ada could not escape the traditional Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) with unsterilized instruments. The practice is known to have led to excessive bleeding and even death of some female victims.

At six years old and recovering from the painful circumcision, Ada was bartered off as a child labourer to a wealthy farmer who sent food items to Mma in exchange for Ada’s chores as a maid servant, a fancy word for a “slave girl.”

Ada received a message from her mother a few months later that her younger brother, Friday, had died, apparently from “kwashiorkor,” a disease linked to malnutrition. Part of Ada’s experience during the war was moving with the farmer to a new farmhouse, where residents dodged bullets and witnessed the devastation of bombs, including “ogbunigwe,” the Biafran-made mass killer.

After the 30-month civil war, Ada returned to Mma, and along with her two other siblings, all joined Umeadi in Lagos. The couple had two additional children, all girls and albinos. Umeadi rejected them and insinuated infidelity. His allegation of adultery was untrue, but Mma was helpless. Ada saw her father verbally and physically abuse her mother, who only sang mournful songs in tears.

Mma’s story is one of strength in suffering, rejection, shame and abandonment in an abusive marriage. While Ada sympathised with her mother, she was disappointed that Mma failed to rescue her daughter from being abused by her father.

Umeadi eventually died in a car crash. Curiously, out of six passengers crammed into a vehicle on that fateful journey, he was the only fatality. Before then, Mma had died in 1978 from prolonged ill-health arising from domestic violence. While Umeadi’s body was taken to Abba for burial, Mma was buried at the Atan Cemetery, Lagos, against Abba culture of “ozu nwada Abba adiato namba.”

With the demise of her mother, Ada took on the responsibility of caring for her albino sisters, who were barely a year old, including soliciting breast milk from a generous woman to feed her younger sister, Tonia.

Ada’s heart-wrenching story, presented in a no-holds-barred style, will resonate with victims and hopefully prick the conscience of society into taking remedial action.

By divine delay, Ada only started menstruation at 15, which prevented a possible ‘in-breeding’ of an offspring from incestuous attacks. She was able to complete elementary education, but could not proceed to secondary school due to a lack of funds.

However, as a private student, Ada did well in the West African Examination Council’s tests and also trained as a Secretary at a Commercial Institute, which enabled her to secure her first job as a Confidential Secretary with a company in Lagos.

Umeadi remarried, and after Mma’s death Ada rented an apartment and moved out of her father’s house with her two sisters. One of them died mysteriously years later in Lagos.

Ada established herself in the media and entertainment industries, working as an award-winning presenter at Radio Nigeria. She also won laurels as an actress, which brought her in contact with Nigeria’s Nobel laureate, Wole Soyinka, after the Ajo Arts Festival in August 1986.

Resilient also featured Ada’s love affairs, including vacations to London and the US.

Returning from her 1988 American vacation, she resumed her Radio Nigeria job and landed a more lucrative bank position, which she declined.

Despite discovering her husband’s previous arranged marriage and other secrets, and enduring domestic violence, arrest and detention for trumped-up charges by him, Ada still raised their two children to higher university degree level, and is a grandmother today.

She supported her husband in his decision to relocate to Nigeria, where he passed on in 2023, leaving her a widow. Resilient is available on the Amazon platform.

An award-winning Journalist, Paul Ejime is a Media/Communications Specialist and Global Affairs Analyst

![]()